Exploring the intersection between arts & neuro-ethics at the INS: a resident physician’s perspective

- Boston Society

- May 29, 2024

- 3 min read

Dr. Tatiana Greige is a PGY-4 neurology chief resident at Boston Medical Center. Originally from France, she competed her medical school training at Université Paris Descartes. Her research interests include stroke in the young, intracerebral hemorrhage as well as the intersection between neurology and the arts. She will be pursuing a fellowship in vascular neurology at Mass General Brigham.

Follow her on Twitter/X @tatianagreige

“What is it like to use neuroprostheses, and why does it matter?”

Interesting, I thought to myself. I realized at that moment that I had never really thought about the experiential dimension when talking about neuroprosthesis. Throughout my neurology residency training, I had read and learned about the different types of neuroprosthesis available, and I had taken care of countless patients with spinal cord stimulators, vagus nerve stimulation or patients undergoing deep brain stimulation, however I had never really thought about the ethical, cultural or legal implications of these devices up until now.

Attending the International Neuroethics Society in Baltimore for the first time this past April was an enlightening and enriching experience. The first panel of the conference talked about the blurred lines between devices, body and mind offering fresh insights and perspectives. Another session that left a lasting impression was the panel discussion called “Mind meets Art: Neurology, Research Participation, and Social Justice.” Through evocative performances and thought-provoking narratives, this panel reflected on both the potential and challenges of the arts to disrupt our perceptions of neurological diseases and the stigma that surrounds them. The role of storytelling (through graphic novels, film, dance) also emerged as a powerful tool for humanizing scientific data and and fostering empathy

As a physician, this conference validated my belief in the transformative potential of arts in clinical practice. It was also a great opportunity to present during the poster session, the Museum Art in Neurology Education Training (MANET) Project, an ongoing collaboration between the Harvard Art Museums and Boston Medical Center’s Neurology department since 2022. The project, consisting of multiple custom-designed, in-person sessions at the Fogg Museum (one of the three Harvard Art Museums) aims to incorporate art and humanities in the residency curriculum. One of our sessions, for example, had touched on the multiple aspects of power through the artworks of Dorothea Lange, Pablo Picasso, and Artemisia Gentileschi. It was fascinating listening to my co-residents discussing hierarchy in medical education, the role of mentorship, and power of dynamics not only between residents and attending but also between physicians and patients, as well as physicians and hospital administration.

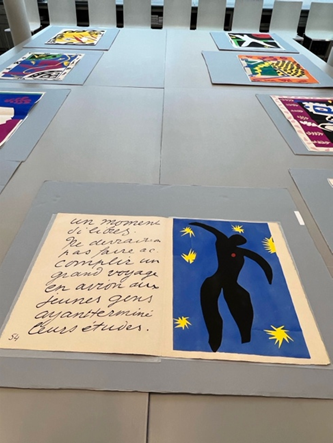

Another session revolved around Henri Matisse’s “Jazz” artwork. “Jazz” inspired thoughtful conversations on the theme of improvisation in medicine, particularly in the context of navigating ambiguity and uncertainty in clinical practice and adapting to unexpected challenges. Neurology residents reflected on improvising in goals of care discussions, particularly when taken aback by unexpected questions. One of my co-residents commented on Matisse’s expressive use of vibrant and bold colors and reminded him that communication often transcends verbal exchanges. Pain and numbness, highly subjective symptoms, are frequent chief complaints evaluated by neurologists. Patients sometimes may find it difficult to adequately convey their experience in words, reminding us of the importance of empathetic communication.

At our last session at the Fogg Museum, the LaToya Hobbs exhibition, a remarkable portrait of an artist and a mother, served a powerful catalyst for conversations about work-life and empathy.

When thinking about my time at the International Neuroethics Society, the following quote from Pierre Lemarquis, neurologist and author, comes to mind “You need medicine that’s purely scientific to address the illness, and medicine that’s a little artistic, to address the person, their humanity. The two are complementary. People need to dream.”

Comments